Download Interview Transcript: Part One (1 May 2013); Part Two (2 October 2013).

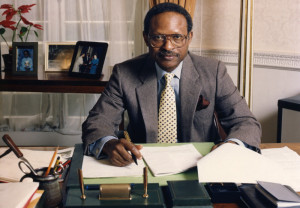

Biography: Anyaoku, Eleazar Chukwuemeka. 1933- . Born in Obosi, Nigeria. Commonwealth Development Corporation, 1959-1963. Member, Nigeria’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations, 1963-66. Assistant Director of International Affairs, Commonwealth Secretariat, 1966-1975. Assistant to Commonwealth Secretary General, 1975-1977; Deputy Secretary General of the Commonwealth, 1977-1983 and 1983-1989; Nigerian Foreign Minister 1983; Secretary General of the Commonwealth, 1989-1999.

Key:

SO: Sue Onslow (Interviewer)

EA: Chief Emeka Anyaoku (Respondent)

Transcript Part One:

[Click here to jump to Transcript Part Two]

SO: This is Sue Onslow talking to Chief Emeka Anyaoku on Wednesday, 1st May 2013 at Senate House. Chief Emeka, thank you very much indeed for coming here to talk to me about the Commonwealth Secretariat from when you joined in 1966 through your time as Secretary General of the Commonwealth.

When you were first approached while you were in your position at the United Nations in New York in 1966, what was your understanding of the Commonwealth Secretariat and the role of Secretary General?

EA: Well, I was actually first approached in December ‘65. My government told me that month that I was to be seconded to the newly established Commonwealth Secretariat. My first reaction was to say ‘No’, I was not prepared to go there because in my view at the time the Commonwealth was a neo colonialist organisation; it had not found a niche for itself; and I wasn’t sure what the Secretariat would be about until I had a discussion with A L Adu, the Deputy Secretary General whom Arnold Smith asked to come to New York to see me.

I talked with him and from what he said I formed the favourable impression that Arnold Smith was a man who was determined to make something of the Commonwealth. So, I agreed and came to London in April 1966. My view of Arnold Smith at the time was that he was determined to make the Secretariat an instrument for Commonwealth diplomacy. In that respect, I’m not too comfortable with the description of the Commonwealth Secretary General as an international civil servant. Arnold Smith laid the foundation of the Secretary General becoming more than a Civil Servant. A civil servant is usually an adviser who advises on policy formation and sees to the carrying out of policies. But Arnold Smith was an international public servant in the sense that he believed that the Secretary General should have a role in the formulation of Commonwealth policies, and this was what he did.

SO: That was very evident from looking at his role in the committee to set up the Secretariat, dated from ’64 to ’65. I’ve seen his papers in the Canada Archives, and they show clearly his dynamism and the proactive approach which he genuinely believed the new Secretary General should occupy. It seems to me he came into office, very much with a goal, a strategy and a purpose to this new role and he was determined to give it substance and formulation.

EA: Absolutely, because there were two schools of thought about the Secretariat. One school which was typified by the New Zealand Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, was that the Secretariat would be like a Cabinet office and the Secretary General should be like a Cabinet Secretary taking notes in the cabinet meetings and doing no more than that. The other school was the Arnold Smith school that believed that the Secretariat had a role to play in shaping the new, the modern Commonwealth and so he stuck to that role. The first and most important Commonwealth declaration was the Singapore Declaration of 1971 which I would describe as a statement of shared Commonwealth beliefs. The difference between that and the subsequent Harare Declaration of 1991 was that whereas the Singapore Declaration was a statement of shared beliefs, the Harare Declaration was a statement of a code of conduct. ‘Shared beliefs’ are there for people to proclaim; a code of conduct is there for people to adhere to.

SO: When you first joined the Secretariat in 1966, in the International Affairs Division under its director, Tom Aston, it was a very much smaller organisation. This was still very much an era, between ’65 and ’71, of laying the foundations and growing the Secretariat. Patsy Robertson has told me that the joke was that every time Arnold Smith went off to a meeting, he came back with a new division.

EA: The Secretariat was established in ’65 as a small organisation. When I joined in ’66, the first assignment given to me by Arnold Smith was to be secretary of a review committee and this was a committee headed by Lord Sherfield. The task of the committee was to look at all the existing Commonwealth organisations and see which ones of them could be integrated into the newly established Secretariat. The review committee sat for a couple of months and as a result of the work of the review committee, the Economic Affairs Division of the Secretariat was created, the Education Division of the Secretariat was created and the Science Division of the Secretariat was created because these had existed as separate individual organisations which were now integrated into the new Commonwealth Secretariat.

SO: The Economics Division had existed, of course, beforehand, and had been staffed entirely by British civil servants.

EA: That’s right.

SO: So, at what point did Arnold Smith start to make a conscious drive to recruit commonwealth expertise?

EA: He began to recruit economic experts after the work of the review committee resulted in the integration of what had existed as a Commonwealth Economic Council as the Economic Affairs Division of the Secretariat.

SO: These also, of course, are the years of considerable political challenges for the new Secretariat with the Rhodesian UDI crisis and the consequent enormous tensions that caused within the Commonwealth, the organisation of the heads of government meeting, the emerging Nigerian civil war, tensions over St Kitts, Nevis and Anguilla, the Gibraltar referendum. These were, as I say, times of challenges for the International Affairs Division. Were you concurrently involved, in your work, with these various challenges, or was Arnold Smith quite careful to make sure that he allocated different roles to different officers? I’m trying to follow his working practices and management of this new international organisation.

EA: Arnold Smith believed in using his colleagues for what tasks he considered that they could perform well. For the Anguilla crisis, he appointed me Secretary of the Anguilla Commission, a nine months operation that was headed by Sir Hugh Wooding, former Chief Justice of Trinidad and Tobago. For the Gibraltar referendum I was also the secretary of the Commonwealth team that went to Gibraltar.

Arnold Smith believed in the Secretariat helping its member countries to deal with political and diplomatic challenges. So, when in the Anguilla crisis which had resulted from the decision of the leaders of the island of Anguilla to secede from the three island state of St Kitts, Nevis and Anguilla, Arnold Smith in discussions with Lord Home then British Foreign Secretary, offered the help of a Commonwealth commission in dealing with the crisis and Lord Home accepted. Consequently, Arnold Smith constituted a Commonwealth team to go and deal with the crisis and asked me to be the Secretary of the team. A similar thing happened over Gibraltar. For many years, several Commonwealth countries at the United Nations had, in their opposition to colonialism, voted with Spain in resolutions that sought to invalidate the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 which ceded Gibraltar to the United Kingdom. Arnold Smith after a discussion with Prime Minister Harold Wilson decided to appoint a Commonwealth team of observers to assist in ascertaining in a referendum what the wishes of the Gibraltarians were.

SO: So, this was Arnold Smith’s initiative, proposing it to the British government?

EA: Well, having not been present at the discussion, I cannot say whose idea the referendum was. All I know is that when Arnold Smith came back from Downing Street, he called me and said that he was going to constitute a team of observers from the Commonwealth and wanted me to be the Secretary of the team. The team went to Gibraltar a few times; I still remember that at the referendum there were 144 votes for joining Spain, and 12,138 for staying British.

SO: Rather like the recent vote in the Falklands referendum?

EA: I believe so. At the following Commonwealth heads of government meeting after the referendum, I remember Harold Wilson saying to his colleagues, “For years your representatives at the UN have been voting that the UK should hand over Gibraltar to Spain. Look at the results of the referendum, what do the figures say?” Whereupon, Julius Nyerere replied, “Well, Harold, in that case we’ll change our votes”.

SO: The people have spoken! I have three questions coming out of what you’ve just said. In those early years what was the relationship like between the Secretary General and Downing Street? I’ve read elsewhere that at critical points there had been frictions and tensions between Marlborough House and King Charles Street. But, as you recall, in those early years what was the relationship like?

EA: Well, at the level of bureaucrats, the relationship was initially at least not excellent because the bureaucrats seemed to prefer to side with the school of thought that would limit the role of the Secretariat to just note taking and implementing the decisions of Commonwealth leaders. The bureaucrats were generally of that ilk even to the extent that the registration of the car of the Commonwealth Secretary General had become an issue. When Arnold Smith wanted ‘CSG 1’, the officials resisted that, but Arnold Smith had his way in the end.

At the political level, it really depended on who the Prime Minister was. Arnold Smith got on very well with Harold Wilson, and also very well with James Callaghan. The friction really occurred with Ted Heath. When Ted Heath became Prime Minister and made it clear that he was going to honour the Simonstown Agreement which meant arms to apartheid South Africa, that was the beginning of the friction between Downing Street and Marlborough House.

SO: You are identifying here friction between political cultures, but also between bureaucratic cultures?

EA: Yes.

SO: And of the challenge to British civil servants dealing with and of having to recognise a new diplomatic actor…

EA: Absolutely.

SO: …which had a legitimate voice – and I use that word “legitimate” very carefully.

EA: Yes.

SO: Having looked at some of the papers of the Commonwealth, I’m very alive to Harold Wilson’s use of the Commonwealth to support British diplomacy – such as in an idea of a mediation team going to Vietnam; in the idea, as you say, of the Gibraltar referendum. When you make reference to the commission in Anguilla, it was followed subsequently (under a Conservative Government) by the Pearce Commission, another commission to solicit grass roots support for a particular settlement proposal.

EA: Yes but the Commonwealth played no part in the Pearce Commission.

SO: So, there seems to be a cross-fertilisation of ideas here between Downing Street and the Commonwealth Secretariat.

EA: Yes, I believe this was the case. Arnold Smith convinced the political leadership in the UK that the Commonwealth was there to be used by its members for dealing with some economic and political challenges and that he as the head of the Secretariat was willing to see the Secretariat contribute to such undertakings. Obviously it depended on the political leadership and what their objective was. Harold Wilson had led the fruitless talks on HMS Tiger and HMS Fearless. He did not involve the Secretariat in the two talks.

SO: From what you observed, was the very fact that Arnold Smith was an experienced Canadian diplomat important in establishing that separate voice of the Commonwealth?

EA: Indeed, it really mattered that Arnold Smith was a Canadian.

SO: And as a white Canadian?

EA: Yes, Canada was a white country without the baggage of colonialism and all that. A real and effective bridge between the old and the new Commonwealth.

SO: Patsy’s also described Arnold Smith as being from the Caribbean, as his family was from Grenada. So there was a slightly different aspect, she said, to his formative political culture.

EA: Well, I would say from my dealings with Arnold Smith which lasted for such a long time that we were not just colleagues, but also became friends. I remember my last visit to him accompanied by Mary Mackie when he was ill in Canada. I had gone to the trouble of going all the way to visit him on his sick bed in Canada. One of Arnold Smith’s greatest virtues was that he was entirely colour blind. There are not many people, whether black or white, whom one describe as being genuinely colour blind. This was one of his strengths as Commonwealth Secretary General.

SO: In terms of his management of the Secretariat: it has been said of other organisations that different divisions, and different elements receive particular attention from the leadership and the others can be left to just bumble along in their own particular way. What was Arnold Smith’s way of working? Was this to foster a dynamic, evolutionary approach to the Secretariat and its emerging divisions? How did he support his particular officers?

EA: Well, Arnold Smith believed in dialogue and he had regular discussions with the heads of the divisions, the directors. At that time there weren’t too many directors. He was naturally inclined to dealing more often with the directors and their assistants of divisions that happened to be working in the areas of his immediate concern and immediate priority. He worked a great deal with the International Affairs Division because the crises that were at the time capable of making or un-making the Commonwealth were essentially political crises. So, Arnold Smith focused very much on the political challenges that the Commonwealth faced at that stage. This is not to suggest that he overlooked the Economic, Education and Science sides of the house.

SO: And they were significant.

EA: Yes, the crises were significant because they were capable of breaking up the Commonwealth. Rhodesia, as it then was, was a major challenge to the continued cohesion of the Commonwealth, and Arnold Smith handled it. You will find this in his own memoirs.

SO: Yes, in ‘Stitches in Time’.

EA: He was involved in seeking to end colonialism in Southern Africa. I accompanied him to a meeting with the then Portuguese Foreign Minister.

SO: Mario Soares?

EA: Yes, Mario Soares. He met Mario Soares more than two times. He first met him on Saba Saba Day – that’s July 7th – in 1974 in Dar es Salaam and then again here in London. Mario Soares was staying at a hotel in Knightsbridge and they talked about Mozambique. I remember that the first meeting on Saba Saba Day was somewhat overshadowed by the forceful interpretation of the speech made by Nyerere into Swahili by Samora Machel the leader of the Liberation Movement in Mozambique, FRELIMO.

SO: Because this contact between Portugal, post the April ‘Carnation Revolution’, with the Secretariat in the run-up to Mozambique’s own first step to full independence the following year in ’75 is not widely known. So, how close were these contacts? Were they discussing developmental assistance, support to FRELIMO as a liberation movement moving to a new government?

EA: Arnold Smith was at that stage urging Mario Soares to persuade the Portuguese revolutionary government to accept the inevitability of the independence of its African territories.

SO: But in July/August General Spinola was still arguing over a different proposal for colonial autonomy…

EA: Mario Soares had personally accepted decolonisation. He was ahead of Spinola who did not seem prepared to grant full independence to their African colonies. Mario Soares had seen that the end of Portuguese control of Mozambique was inevitable and in his discussion with Arnold Smith was interested in how the Commonwealth experience would be useful to the Portugese speaking countries in Southern Africa. Arnold Smith also met with Samora Machel who briefed him on FRELIMO’s continuing struggle for the independence of Mozambique.

SO: Sir, are you aware whether Arnold Smith, in any way, sought to encourage Samora Machel to keep white skills in the country? Part of Mozambique’s challenge post-independence was to deal with the abrupt departure of Portuguese settlers, but also their physical destruction of infrastructure, and of industry?

EA: Well, you see, there were two schools of thought in Portugal. One school was in support of what you would call a ‘scorched-earth policy’, that is totally abandoning Mozambique to its fate as the French had done in Guinea. In being compelled to grant independence to Guinea, the French had gone as far as letting prisoners free from the prisons.

The other school of thought to which Mario Soares clearly belonged was “let’s give them independence, but let’s retain relations with them so that we can work with them”. It was this second school of thought that won the argument because Portugal granted independence to Mozambique in two stages. First, there was the provisional self-government which was headed by Joaquim Chissano for almost a year while Samora Machel remained in the bush still leading FRELIMO. It was after about nine months when full Independence came that Samora Machel, with his troops, marched into Maputo.

SO: So, Arnold Smith’s ideas were to offer training, and human skill development? Did you, as a more junior officer in the Secretariat, have to follow up on any of these exploratory offers?

EA: Arnold Smith laid the foundation; but the formal offer to Mozambique of Commonwealth assistance in the development of human skills was made by Sonny Ramphal. On becoming Secretary General in July 1975, Sonny Ramphal asked me to lead a team of three secretariat officials – John Sisson, Roland Brown and myself – to Mozambique to explore the possibility of Commonwealth assistance to the emerging nation. At that time it was Joaquim Chissano’s transitional government which was in power. We went and discussed with the transitional government the possibility of Commonwealth training of Mozambicans as they prepared to assume full responsibility for their government. It was on the basis of our report that a formal Commonwealth Assistance Programme for Mozambique was established thereby laying the foundation for an eventual Mozambican close relations with the Commonwealth which culminated in the country’s admission into the membership of the organisation.

SO: So, this pre-dates Mozambican independence and Rhodesian/ Zimbabwe transition in 1979-80. In fact, there were early supportive moves from the Commonwealth right from the start of Mozambique’s independence?

EA: Yes.

SO: It’s interesting to make the comparison of Commonwealth assistance offered to Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, and also Commonwealth assistance offered to South Africa at the point of transition.

EA: Yes.

SO: So, early templates were developed and then later elaborated?

EA: It was the same idea that had to be developed in accordance with the circumstances in the three countries.

SO: Very much so. Just to go back to Singapore in 1971, a Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting which at that point lasted ten days. You were of critical importance, together with Ivan Head, in drafting the Singapore Declaration. Where did the intellectual ideas behind this come from? Was there much resistance in the wider heads of government to such formulation?

EA: I think it would be fair to give some credit for the intellectual origins of the Singapore Declaration to Ivan Head and Pierre Trudeau. The draft was a three-cornered effort because of the inputs into it by the Secretariat and the State House in Lusaka. At the CHOGM in Singapore, it was really driven more by Kaunda than by Trudeau, because it was Kaunda who in the face of the crisis over arms supplies to South Africa pushed the idea of defining the Commonwealth. He argued that the idea of defining the character of the Commonwealth was important because by acknowledging the Commonwealth as an association of equal sovereign states, all would be accepting the right of individual members to determine and pursue their independent policies. While at the same time defining the shared fundamental principles of the association would make it easier for member governments to recognise and avoid policies that go against those principles. Thus it would be easier to deal with the question of apartheid because you cannot believe in non-racism and in freedom and democracy, and at the same time be supporting an apartheid regime. By agreeing to that and to the decision to set up a committee of eight foreign ministers to deal with the crisis, it made it possible for Ted Heath to save face. For as they say, when a problem seems immediately insoluble, it should be assigned to a Royal commission [Laughter].

SO: Sir, please may I just ask you about President Kaunda’s particular role. You’ve used the word “inter-mestic” in your memoirs, “of domestic issues that then have international ramifications and require Commonwealth assistance”. Is there also a dynamic of individual Commonwealth leaders using success through the Commonwealth to feed back into their domestic environment? As that gives them additional legitimacy?

EA: Yes. Take elections, for example. Commonwealth observance of elections legitimises the election and makes it easier for the parties who have lost to accept the result if the election is judged to be free and fair by Commonwealth observers. And this works both for the governing and the opposition parties.

Zambia was an example of this. As I told the story in my book, I sent a team of Commonwealth observers to Zambia for the 1991 elections and had asked Patsy Robertson who was their spokesperson to let me know the moment that the returns established a decisive trend. By sheer coincidence, Patsy called me while I was having lunch alone with Nelson Mandela in the Carlton Hotel in Johannesburg. Patsy told me that it had begun to appear from the announced returns that the opposition party leader, Frederick Chiluba was going to win, but that at the same time, the signals coming from Kaunda’s camp were pointing to a rejection of the outcome of the elections.

I immediately called Kaunda and informed him of the brief I had received from my people. He told me that his supporters were reporting to him that there was a significant manipulation of votes by the opposition party. Whereupon I said to him, “KK, my people, the Commonwealth team have told me that their verdict was going to be that the election was generally free and fair, it would be very difficult for it to be invalidated.” I strongly advised him to agree to accept the result.

Mandela was listening to this conversation. I said to him “KK, I believe that your brother, Nelson Mandela, who is here with me would like to say hello to you” and then gave the phone to Mandela. He spoke to KK offering him his sympathy.

After that I tried to call Chiluba. I didn’t get Chiluba immediately but I got one of the leaders of his party, Vernon Mwaanga, an old friend of mine. I said to Vernon, “Look, my people tell me that you’re winning. Congratulations. But I want to talk to Chiluba because I would like to strongly advise him that in victory, he should treat KK as a father of the nation and a senior citizen”. Vernon agreed and gave me Chiluba’s telephone number.

I called and spoke to Chiluba. After congratulating and advising him on how he should treat KK, I told him that KK had assured me that he would accept the verdict of the election and would himself personally conduct Chiluba around the State House in handing over the government to him. Chiluba told me that he accepted my advice. Accordingly on leaving the State House, KK was moved to a house belonging to a government para-statal.

However, after about seven to ten days, a group within Chiluba’s party succeeded in getting him to change his attitude to KK. Vernon Mwaanga was the leader of the group. KK was then thrown out of the house. His personal effects were searched and ransacked on the allegation that they were looking for books that he had removed from the State House library. And his pension was stopped.

I did not know of any of this until some five weeks later when I went to Arusha for a roundtable arranged by Salim Salim, then Secretary-General of OAU, on democracy. KK attended the roundtable and we were staying at the same hotel. KK told me that he would like to see me and I, treating him as an ex-senior leader, went to his room to see him. He poured his heart out to me, telling me of how he arrived in Arusha at 5am by courtesy of a special flight arranged by President Moi of Kenya, how he was thrown out of the government-owned house in Lusaka, how his two sons had teamed up to find accommodation for him, and how his pension payment was stopped. He was evidently in need for funds. I thought that it was quite remarkable and much to his credit that after 27 years as leader of Zambia he had no savings.

SO: He was a man of integrity; he is a man of integrity.

EA: Of great integrity. I was so moved that on my return to London, I called Chiluba and said to him, “I’d like to come and see you”. Chiluba agreed. So, I flew down to Lusaka and had a meeting with Chiluba. I asked him, “How could you treat KK in the manner that he had narrated to me”. I reminded him of the conversation we had at the end of the elections. His reply was that the pension arrangements approved by KK’s government for the President and members of parliament had been excessive and that the government and the country could not afford to pay that. I replied, “If you cannot afford that, why don’t you pay him something in the interim while you decide what you can afford?” I reminded him that he himself would one day become an ex-President and that it would be in the interest of all to have a settled government pension arrangements. At the end we agreed that I should recommend a package to him and his Government.

I went to see KK after that and was quite upset by the condition in which I found him. The house where he was and the surroundings were relatively poor; his children could not afford anything higher than that. So, I came back to London and asked my International Affairs Division to collate the practices of about five countries, including developed and developing countries, of how they treated their ex-Heads of Government. It was on the basis of that that we prepared a package which I recommended to Chiluba. Eventually he and his government adopted the package.

SO: Sir, did you use this experience to inform your approach when you were using ‘good offices’ in the 1990s – approaching African leaders whom you had known personally through the Commonwealth Secretariat, and also when you were Foreign Minister of Nigeria, to encourage them to accept the need for popular expression of voting preference?

EA: Yes.

SO: I was just wondering how formative experiences played into your negotiating skills, persuading people who had been in office in one-party states, or no-party states, the logic of allowing multi-party elections?

EA: Well, you see, it goes back to my determination from the start of my tenure. After my election, I spent about six months in retreat before I assumed office on the 1st July, 1990. One of my firm decisions was that the Commonwealth must deal with its internal contradiction because on the one hand, the Commonwealth was rightly championing the cause of non-racism and democracy in South Africa, while on the other hand, the same Commonwealth was tolerating among its membership military dictatorships and one-party states that were clearly non-democratic regimes.

Such a situation provided material for some of the right wing newspapers in the UK, in Australia, in Canada and elsewhere to criticise the Commonwealth and cast doubt on the usefulness of the association. I was determined to change that situation. So, when after the Harare Declaration which prescribed a code of conduct for Commonwealth countries, I used that as the basis for persuading the Heads of government who were running either one party states or military regimes to accept that the Commonwealth principles were meant to be kept and lived by.

SO: Sir, with respect, it’s one thing for heads of government to accept aspirational declarations that could be said to be part of process, and then to confront the reality of what that means for their own particular position in-country.

EA: That’s where personal chemistry, personal relationships and personal confidence became important. I mean, in discussions with people with whom you have established good relations and mutual self-confidence making them believe you and accept what you’re saying. There are two examples of this. I had long conversations with Kenneth Kaunda whose starting point was to have a referendum to decide whether there should be a multi-party state or not in Zambia. Eventually I persuaded him to do away with the referendum in the same way as I persuaded France-Albert Rene in the Seychelles who was going to have a referendum to determine whether his country should move from one-party to multi-party government. But I was not able to persuade Kamuzu Banda on a similar point in Malawi. Banda had sent his minister to see me and I sent him a message using the same arguments that I had used with KK. But Banda insisted on going to a referendum before changed to a multi-party state.

SO: Sir, this question of personal chemistry, mutual confidence and personal knowledge with African leaders involved that intangible and vital question of trust.

EA: Yes. Yes.

SO: Had you developed a particular, lawyerly, technique for opening the discussion to show the other side of the argument? You said you persuaded them. I’m intrigued to know how?

EA: I believe that when seeking to persuade leaders, the technique I that used which worked was to start with an appreciation of their problems and challenges. You must appreciate their problems and show that you really understand what they’re struggling with. Generally, it’s coping with opposition parties who in a number of cases were deriving some of their oxygen from outside elements.

SO: Not necessarily just oxygen!

EA: Well, I mean support. In 1998 I convened a Roundtable of Commonwealth leaders in Africa on the theme of sustaining democracy in their countries. I discussed with them in a room where they were alone with me – the only other person with us was Frene Ginwala the speaker of the South African parliament at the time whom I had invited to be the Rapporteur. To my question about the main challenges they faced in adopting and sustaining democracy in their countries, all of them, to a person, spoke about outside interests seeking to undermine them, not only through verbal encouragement but also through supply of funds to their opposition parties. In Zimbabwe, for example according to President Mugabe, the Heritage Foundation in the United States and the Westminster Foundation in London were providing encouragement and funds to his opposition party led by Morgan Tsvangirai and he claimed that his Government had evidence of bank transfers.

SO: So, this completely counteracted any argument of a loyal opposition?

EA: Yes, that was their contention. And come to think of it, I doubt if there is any African lexicon where you have the concept of “a loyal opposition”. The common African lexicon is either political friends or political enemies and the only natural treatment of enemies is to put them to rout.

SO: Sir, this is fascinating because so much emphasis is placed on political cultures coming out of liberation struggles. You have contestation for absolute power; winner takes all. But this idea that actually there are more complicated, historic political roots – with ‘political’ taken in its broadest cultural context.

EA: Yes, because culturally speaking, there is only one thing that you do to your enemy. You eliminate them. If you have no culture of loyal opposition and all the culture you have is that of political enemies, you would naturally want to eliminate them. So, in politics, the idea of winner takes all is much more natural to some societies, whereas in the Commonwealth, the basic culture is always to seek Commonwealth consensus.

SO: Sir, could I also put to you though, this question of racism. You made reference to this earlier. How far do you feel there was also an element for individual African leaders to be more open to your style of empathy and negotiation, precisely because you came from Nigeria? Of course, Nigeria has a very different political culture to Kenya, or to Malawi, but was there a Pan-African ideal subtext in your appeal, rather than a perceived external, white admonition?

EA: Yes my origin and nationality was a great help because it was easier for them to accept critical observations from me being an African; and of course, I put that factor to maximum use. When I said that I would start my discussions with them by appreciating their problems, I appreciated their problems from an African point of view because I readily understood them.

SO: Also as a Nigerian? Your country has been through its own tumults and traumas, and yet you have successfully sustained your patriotic commitment to your country. You have been a loyal opponent. So, were you able to draw on your own particular experience?

EA: Yes. It helped – the fact that I had strongly disagreed with the dictatorship of General Abacha but remained as patriotic a Nigerian as any other was an example that I constantly referred to.

SO: Sir, in your staff’s support for your work in ‘good offices’, were you actively encouraging them to adopt a certain style of negotiation, a certain way of interaction? I’m just wondering to what extent your leadership from the top was deliberately structured to ensure that your staff supported your individual advocacy to best effect?

EA: Well, it’s something that I was always mindful of. An example here was my very first meeting with F.W. de Klerk in his cabinet room in Pretoria. The meeting was on 1st November 1991. The first time that I told him that I had come to discuss with him how the Commonwealth could help the process of realising his publicly stated objective of transforming the situation in South Africa, his first reaction to me was that the Commonwealth was a very hostile organisation to South Africa by consistently advocating sports and trade sanctions against South Africa; accordingly he did not need help from the Commonwealth; that South Africa had friends in Europe, Africa and elsewhere.

SO: Very much the mindset from the National Party.

EA: Yes. He said to me, “You know, we have friends in Europe and Africa; we don’t need the Commonwealth”. And I said to him, “Mr State President, I thank you for the candour with which you have spoken to me; I owe it to you to reply equally candidly”. I believe that your greatest challenge is how to create confidence among your different ethnic racial groups in South Africa. Look at my team here”. I had with me, Moni Malhoutra, an Indian; Stuart Mole, a Brit; and Moses Anafu, a Ghanaian. I went on to say to him, “You know, Mr State President, the Commonwealth can therefore relate to every section of your population, and what I have come to offer you is help in building confidence among the different sections of your population.” To give State President de Klerk his due, he immediately took the point. So at the end of our meeting, he invited me to join him in meeting the press. The press conference took place in the atrium of the Union Building. Our second joint press conference was in the morning of November 18, 1993 following the agreement by all the parties at Kempton Park the previous night. I’ll never forget that press conference because as soon as F.W.de Klerk finished his comments with some kind words about my contribution to the just concluded negotiations, the first question was put to me by a white South African journalist who said to me, “Mr Secretary General, the State President has spoken about your help to our country. What about your own country?”, there had the same night of the conclusion of the negotiations in South Africa been a military coup d’etat by General Abacha in Nigeria.

SO: Had you known that?

EA: Yes because at about a quarter to midnight that night my Nigerian Special Assistant had brought to me a note in the conference hall at Kempton Park where we all were, saying that there had been a coup in Nigeria. I looked at the journalist straight in the face and said, “Well, I’m sure you would appreciate that it’s human nature to deal with one problem at a time”.

SO: Sir, you’re remarkably adept at thinking on your feet!

EA: I remember that F.W. de Klerk whispered to me, “You’re a very experienced diplomat”.

SO: Which is true! Sir, from what you’re saying, it was the example of your Commonwealth team, with their various national origins but clearly working together.

EA: Yes.

SO: It’s also your team: you’ve mentioned Stuart, you’ve mentioned Moses Anafu, who of course was intimately involved in those discussions and the Commonwealth observer groups going down into Kwazulu Natal at the time. So they had the benefit of seeing your particular negotiating style?

EA: I believe so.

SO: How did structures and techniques of negotiation transfer? Did you have debriefings on coming back to Marlborough House on how best to proceed thereafter?

EA: I think that the most effective way of transferring techniques is by enabling colleagues to be present at the negotiations. Those who were present and who accompanied me to these discussions saw how I was handling the discussions, and I’d like to believe that they would have learnt from that.

SO: This then suggests that Moses Anafu, as a Ghanaian, had that unique African advantage again?

EA: He too, yes, because I can recall two occasions when he did very well. One was in Zanzibar and the other was in Lesotho. In Zanzibar, I tried to broker peace between the ruling party and the opposition party, CUF, particularly after the elections. I left Moses behind and Moses succeeded eventually in getting them to agree to a memorandum that he and I had prepared.

SO: Did you delegate complete autonomy to him, or was he regularly checking back?

EA: Well, I delegated to him authority to negotiate with the parties after leaving behind the memorandum as the basis of his negotiations. The memorandum had to be modified from time to time in consultations of course with me. I then went back for the formal signing and celebration of the agreement by the parties.

SO: Sir, what were the relations like between you and your supporting team with the South African Foreign Minister and his team? You’ve spoken very much of your success in reaching F.W. de Klerk and then in providing support for the transition negotiations; but I just wondered about the Department of Foreign Affairs?

EA: They played very little part in the negotiations in which I was involved.

SO: Was that your conscious choice to concentrate on the head of government?

EA: Absolutely. I knew that F.W. de Klerk was a man who was driving the change. I must say that my confidence in F.W. de Klerk was higher than my confidence in Foreign Minister Pik Botha, in terms of their capacity to effect the changes they were advocating.

SO: Is that because of your assessment of where de Klerk came from, and where his constituency was? That he was coming from the right of his party, having been leader of the Transvaal National Party. Leaders from the right are often able to innovate…

EA: Absolutely.

SO: … in a way that those who come from Centre Left are not.

EA: Absolutely. Those from the right are usually more credible within their party. So, if you get a leader from the right who is persuaded about change, he or she is likely to effect that change much more readily than a leader from the left. Pik Botha was known for years as saying the right things. He was a liberal. He represented the liberal wing of the National Party, but at the end I believe that the deal had to be done not between the liberal wing of the party but between the right wing. F.W. de Klerk, I had seen him in ’86, when the Eminent Persons Group went to South Africa. He was then Minister for Education. De Klerk was as right wing as they came. If you had asked me then who were the three most right wing politicians in South Africa, I would have said P.W. Botha, Magnus Malan, and F.W. de Klerk.

SO: Really. Not Chris Heunis?

EA: No. Chris Heunis was a liberal. Chris Heunis was just a shade above Pik Botha. Chris Heunis was the Minister for Constitution. Chris Heunis sounded reconciliatory. If you had asked me to name two or three who were in the Liberal wing, I would have said Pik Botha and the then Minister of Finance.

SO: Barend du Plessis.

EA: Yes, Du Plessis was the man who said to us that he found it difficult to have to build three hospitals instead of one under apartheid.

SO: Because the tri-cameral parliamentary arrangements required separate racial facilities?

EA: Yes, a hospital for the whites, a hospital for the coloureds and a hospital for the Indians. Of course the Africans were never mentioned; I would have classified him as belonging to the liberal wing of his party just like Chris Heunis.

SO: Sir, did you use the same political reading of the situation when you talked to Daniel Arap Moi of Kenya? Calculating that there were elements within KANU that he could direct and control to lead to multi-party elections, whereas somebody who was, say, from a more liberal technocratic wing of the party could not deliver change? In other words, as in Soviet Russia under Gorbachev, because of the structure of the system, change had to come from the top?

EA: Every situation was different. In the case of Kenya and Arap Moi, after several conversations with him, I persuaded him to accept that I would send a constitutional expert to come and help Kenya revise their constitution, to adapt it to the requirements of a multi-party state.

SO: Did you select an African?

EA: Yes I selected Professor Ben Nwabueze from Nigeria, a widely acknowledged constitutional expert. Ben Nwabueze knows the constitutions of most African countries and has written profusely about them. He is a great intellectual constitutional lawyer and a highly respected authority. I sent him to Kenya and he helped them to revise their constitution to serve the needs of a multi-party state. Then after that, when they held their elections, as I narrated in my memoirs, I had to fly there to deal with the resultant crisis.

The crisis involved Ken Matiba, Mwai Kibaki and Odinga Oginga. Mwai Kibaki had led a break away party and had won about 646,000 votes; Odinga Oginga about 910,000 votes and Ken Matiba about 1.4 million votes as against Moi’s approximately 1.9 million votes. The three claimed that Moi, having won far less votes than their combined votes, had no legitimacy.

I held meetings with them stressing to them the implications of their having fought the elections as different political parties. I reminded them that in the recent elections in the United States of America, the votes of the Republican party and Ross Perot who ran as an independent, taken together were higher than the votes for the Democratic party whose candidate became the President.

SO: But there you’re suggesting a process whereby people buy into elections because each believe they can win, but then that turns into ‘elections they must win’?

EA: Yes, I was saying to them that Moi having scored the highest votes as provided in their constitution had to be declared the winner but that I would endeavour to persuade Moi to agree to an arrangement that would allow greater accountability and avoid the “winner take all” syndrome. They agreed and that was how the crisis was resolved.

SO: Was this your personal hard-fought diplomacy, or is this again delegating to a particular team?

EA: No. I handled this myself by holding the meetings with Ken Matiba, Odinga Oginga and Mwai Kibaki; it was not a situation that I could delegate to colleagues in the Secretariat.

SO: So this is one on one diplomacy?

EA: It was first “one-on-three” diplomacy, because I met these three leaders together, and one-on-one with Moi accompanied in both cases by one assistant.

SO: Sir, may I suggest that in addition to being empathetic, gaining trust, drawing upon African networks and skills, you also had to have a remarkable amount of personal stamina?

EA: I don’t know about that. [Laughter]

SO: Thinking of the time investment, and patience.

EA: Yes, time and patience. And this experience was not limited to Africa. I remember that my intervention in Bangladesh also demanded a lot of time and patience. When I went there, you know, the two political leaders were women: Begum Zia and Sheikh Hasina. Begum Zia was the Prime Minister; she had become Prime Minister following the assassination of her husband who had been the Prime Minister.

My first meeting with the leader of the opposition party, Sheikh Hasina, was held in her sitting room. She and I were sitting under the portrait of her father, Sheik Abdul Rahman, the first Prime Minister of independent Bangladesh who with his entire family had been killed in a military coup d’etat. She was lucky to be out of the country on that fateful night. That was how she was spared. She was full of emotion, looking as we talked, at the photographs of all her family, uncles and siblings, all of whom were eliminated with her father. I was personally quite moved by her emotion. I believe that she recognised from my voice that I was very moved, especially when I then said to her, “Sheikh Hasina, even if a thousand people who were responsible for this atrocious tragedy were to be tried and executed, that surely cannot bring him and your other family victims back”. I looked at her straight in the eye and said, “Is it not better to think of how to get this country to a situation where such tragedy should never, never again happen? I have come here to help in dealing with the seemingly endless feud between you and Begum Zia which has brought continuing violent protests in your country”.

I then put forward a proposal that I would want to send a trusted, experienced representative to come to Bangladesh to hold discussions with her and Prime Minister Begum Zia with a view to finding a formula for mutual accommodation between their two parties. She accepted my proposal and so did PM Begum Zia with whom I had two meetings. Consequently, I sent as my representative, Sir Ninian Stephen, an Australian retired judge who spent weeks in Dhaka brokering peace between the government and the opposition parties.

SO: Sir, in addition to presenting the awful logic that her family could not be brought back but that she should be encouraged to move forward to make sure that there was never again a repetition of that violence, did you draw upon the historic contribution of the Commonwealth to the recognition of Bangladesh back in 1971, to say ‘We are established friends of Bangladesh’?

EA: Yes, I told her the story of how I was directly involved in getting African recognition for Bangladesh and of my meeting with her father at the CHOGM in 1973 in Ottawa at which I was the Conference Secretary. This of course had helped in establishing a personal rapport between us.

SO: Yes, because that international diplomatic recognition of Bangladesh independence was enormously contentious for Nigeria.

EA: Yes it was.

SO: For Bangladesh, in ’71. You had contacted Tanzania and …?

EA: Arnold Smith had sent me on a mission to West Africa – Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ghana and Nigeria – and I deliberately went to Nigeria last. I wanted to be sure that I got the others and particularly Sierra Leone and Ghana to agree before going to Nigeria. My visit to Ghana was within the first couple of days of the Acheampong coup. As I told the story in my memoirs, faced by two well armed soldiers standing behind General Acheampong opposite whom I sat in his office during our meeting, I was scared of reaching out for my scribbling pad in the inside pocket of my jacket.

SO: In case they thought you were reaching for a weapon?

EA: Yes. That’s right. Because the two soldiers behind him had their guns pointed in my direction. The Foreign Minister and the Cabinet Secretary were present at the meeting. I was happy when at the end of our meeting, Acheampong agreed to Bangladesh joining the Commonwealth which was the most formal way to recognise the new country. The difficult one was Nigeria but fortunately I was able to persuade General Gowon, the Head of State, that Nigeria should not oppose the admission of Bangladesh into the Commonwealth.

SO: Was it because you persuaded them of the logic that they shouldn’t oppose it?

EA: Yes. The difficulty in Nigeria was because the day before I got to Lagos, some local newspapers had carried the headline “NO TRUCK WITH SECESSION”. They viewed the emergence of Bangladesh as secession from the established state of Pakistan. Having fought a civil war to prevent the secession of Biafra from Nigeria, the newspapers sought to discourage the Government from recognising Bangladesh.

SO: Sir, what you’re suggesting here then is that as Commonwealth Secretary General- and your position as a proactive, international civil servant who then became a political actor – and I’m using the word “political” in inverted commas – you built upon your enormous institutional knowledge and your personal engagement at critical points in the Secretariat’s history?

EA: I think that’s a fair way of putting it. But I would still be reluctant to use the word “civil servant” because the debate from the beginning of the Secretariat was whether the Secretariat would be just a civil service, or a proactive and active institution of the Commonwealth.

SO: Given your extraordinary longevity of service to the Commonwealth – as you said when we started talking it was 34 years – do you feel then that longevity of other officers was a benefit throughout that time? I know the pattern of appointment for three consecutive terms then was revised and revisited. But with that comes an institutional leaching, a depletion of people’s personal experience and knowledge. So, organisations change over time. The Secretariat you joined in 1966, at the beginning, was a very different beast to the Secretariat that you left in 2000.

EA: That’s right. Well, I saw and was involved in the process of change in the Secretariat, particularly when I became the Secretary General. But I think the advantage I had was that having witnessed it all, having been part of the process I could draw on that experience in my activities and in my relationships with heads of government. Intervening to help resolve what I described as “inter-mestic” issues in several Commonwealth countries was a constant feature of my tenure as Secretary-General. I did not write in my memoirs about all the interventions in which I was involved, for example, I said nothing about my intervention in Pakistan during a potentially destabilizing disagreement between the President and the Prime Minister.

SO: No. I was struck by that gap.

EA: I was involved in what amounted to preventing a potential military coup at the time in Pakistan.

SO: In what way, Sir?

EA: There was a major crisis between the Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif and the President, Farooq Leghari at the time. The President had the sympathy of the judiciary; the Prime Minister had the strong support of the Parliament and government, while the military were expressing some disquiet. I went to Pakistan and had long conversations with the Prime Minister and the President, impressing on them the need for accommodation and perhaps calling early elections which they both accepted.

SO: But, Sir, how were you alerted that the political situation in Pakistan was becoming so tense that it was highly likely there would be military intervention?

EA: I reached that conclusion from my discussions with my contacts here in London including the High Commissioner.

SO: So, again it’s the question of personal networks. It strikes me that this is where the Commonwealth has really its ace, in its personal networks.

EA: Yes. My last observation is that the strength of the Commonwealth in terms of its capacity for diplomatic work lies in its formal and informal, personal relationships. The Commonwealth unlike any other comparable international organisations is not just an association of governments. It is also an association of peoples, and professional groups. The contacts that are generated through these associations underpin the work that goes on at the governmental level.

SO: So, this global sub-system in a way is working against the current drive for technology, for substitution of human contact. You’re emphasising the enduring value in fact…

EA: Of human contact. Yes.

SO: I think, Si, I should end it there. Thank you very, very much indeed.

[END OF AUDIOFILE PART ONE]

—————————————————————————–

Key:

SO: Sue Onslow (Interviewer)

EA: Chief Emeka Anyaoku (Respondent)

MM: Mary Mackie (Chief Emeka Anyaoku’s Personal Assistant)

Transcript Part Two:

SO: This is Sue Onslow talking to Chief Emeka Anyaoku on Wednesday, 2nd October, 2013. Chief, thank you very much indeed for coming back to Senate House to talk to me for this project. I wonder if you could begin, please sir, by talking about the preparatory process leading up to the Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings.

EA: Well, the Secretariat does essentially three things. First, it consults on a continuous basis with the host government on arrangements and logistics for the meeting. And second, it prepares the preliminary draft agenda in the form of suggestions to governments for their comments and additions if they felt necessary; and then in the light of that, prepares memoranda on the issues involved in the agenda. And then thirdly, it also considers what possible controversies, what possible challenges, particular heads of government meeting will face, and deals with those by consulting the governments concerned and talking to heads who are likely to be involved in resolving what the challenges are. And I must also add to the first point about consulting with the host government that since 1973, when the retreat was introduced, the consultation would also include arrangements for the Retreat.

SO: So having identified the host government, then there is close coordination with the Secretariat to ensure the administrative arrangements are as smooth as possible. In the preparatory process, how much international travel is involved for International Division to coordinate with other governments having identified the potential storm clouds that inevitably loom before Commonwealth heads of governments meetings?

EA: Well, there’s a bit of travelling to start with in respect of the arrangements and logistics: usually travelling between the Secretariat and the host government, which is done by the conference secretary who is the Director of the Political Affairs Division, and then there’s also travelling which is done by the Secretary General himself to deal with the major issues coming up at the meetings, and he would usually ask, in addition to his private office staff, the head of the political affairs division to accompany him. There are not a fixed number of travels involved; it often depends on the issues coming up at the heads of government meeting; where there are challenges that require wider consultations, the Secretary General would inevitably do more travelling than in other cases.

SO: You have been intimately involved in the organisational details of Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings, both in your position as Assistant Director in International Affairs, and then moving up the hierarchy within the Secretariat to the position of Secretary General. Arnold Smith had, obviously, a particular style of diplomacy in managing these meetings which was similar, but not identical to Sir Sonny Ramphal. The first Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting that was abroad, of course, was Singapore in 1971 – being the first meeting outside London after the special meeting in Lagos in January 1966. You were not yet at the Secretariat at that particular point.

EA: No, I was not at the Secretariat at the time of the special meeting in Lagos but I was there for the Singapore meeting.

SO: Were you involved in international travel to try and smooth the way, in any way, shape or form, before the Singapore meeting?

EA: Not for the Singapore meeting, because at the time of Singapore meeting I was Assistant Director. Bill Peters was my director. At that time it was still called the International Affairs division, and it was he who did the travelling between London and Singapore.

SO: Was there a great deal of international travel beforehand? The storm clouds at that particular meeting were the British government’s decision to revive the issue of helicopter and arms sales to South Africa, under the Simonstown agreement, but the meeting was also against the background of British Prime Minister Ted Heath’s determination to push Britain’s application for the European Economic Community. At the same time there were looming tensions within the then Pakistani state, between East Pakistan and West Pakistan. So were you involved in…?

EA: Well, I accompanied Arnold Smith to a very crucial meeting that he had at Chequers with Ted Heath over the issue of possible arms supplies to South Africa. And also, I accompanied Arnold Smith the following year to Pakistan on the issue of Bangladesh emergence as a sovereign state. But when I went with Arnold Smith to Pakistan, I had become the director of the division. In the case of preparations for Singapore, Arnold Smith travelled quite a bit because the issue was very challenging. I cannot now recall the precise list of the countries he visited but I remember that he travelled to the Caribbean, to Africa and to India to consult with Heads of Government over the challenges that were due to come up in Singapore.

SO: So in trying to hear from heads of government their particular views, was Arnold Smith trying to reach a degree of consensus before the Singapore meeting?

EA: Well, yes, actually the purpose of his intervention was to soften the determination of Ted Heath to go ahead with his stated policy, while at the same time trying to soften the reactions of some of the heads of government with a view to avoiding, or at the least limiting the adverse impact of the conflictual views on the cohesion of the Commonwealth.

SO: How clearly do you recall that meeting at Chequers?

EA: It was not an easy meeting. It was a meeting that happened about 10 days after Julius Nyerere, had been to Chequers to see Ted Heath. And on his leaving Chequers, he told Arnold Smith that he’d had a very difficult meeting with Ted Heath, that Ted Heath seemed adamant. And so Arnold Smith went to Chequers with the benefit of the briefing from Nyerere and so sought to soften Ted Heath’s determination to go ahead with the policy of resuming arms supply to South Africa. He didn’t entirely succeed.

SO: I’m not surprised!

EA: [Laughter].

SO: Ted Heath was a colleague of my father’s; I met him a couple of times, so, no, that does not surprise me.

EA: Yes.

SO: But how closely was Arnold Smith also coordinating with Lee Kwan Yew as the host prime minister, the host head of state? You talked about his tours of the Caribbean, of Africa, trying to –

EA: Yes, he also went to Singapore to consult with Lee Kwan Yew.

SO: Of course. So in that case there would have been close collaboration, particularly with the host government on how to manage this explosive issue on top of the Rhodesia crisis?

EA: Yes indeed.

SO: So do you recall, or were you aware of, Lee Kwan Yew’s particular input in this?

EA: Lee Kwan Yew’s primary concern was to have a successful heads of government meeting. His primary concern was with how to manage the situation between Ted Heath and most of the African heads of government who were the most critical of the policy. And Arnold Smith discussed with Lee Kwan Yew the idea of setting up a foreign ministers committee as means of diffusing the crisis.

SO: The special study group on Indian Ocean security.

EA: That’s right. The way in which the crisis was diffused at Singapore was by appointing an eight member Foreign Ministers’ committee to deal with the issue of security of the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic and so provide Ted Heath with a face-saving device, really.

SO: And this is the era before the innovation of the Retreat. Do you have any recollection of where the idea of the study group came from? Because there wasn’t the possibility of heads retreating into an informal setting to resolve the issue among themselves.

EA: It was an idea that Arnold Smith and Lee Kwan Yew had discussed and an idea which Lee Kwan Yew subsequently put to the executive session of the heads of government meeting for consideration and adoption. There was no Retreat at the time, so it had to be put to them in an executive session.

SO: I’m just thinking of the management of diplomacy: whether Arnold Smith and Lee Kwan Yew had thought, as a way to resolve this, to take it out of a very fractious heads of government meeting, might be to delegate to two officials.

EA: No, they didn’t think about it that way. What they thought, and which happened, was that once he and Lee Kwan Yew discussed and agreed that a possible way out was through the setting up of this eight member committee of foreign ministers, Arnold Smith then took it on himself to sell the idea to some of the African heads of government concerned, and Lee Kwan Yew undertook to sell it to Ted Heath. I did accompany Arnold Smith to at least three such meetings with some African Heads of Government.

SO: I see. Now I understand the pattern of diplomacy.

EA: Yes. So Lee Kwan Yew was talking with Ted Heath and Arnold Smith was talking with the other heads of government.

SO: And there were a much smaller number of heads then.

EA: Yes.

SO: Absolutely, there were only 22, so it was a very different forum.

EA: Yes.

SO: People talk of the innovation of the Retreat at Ottawa in 1973, and Trudeau’s enormous intellectual input into the Commonwealth, but I’m particularly interested in a subsequent meeting in Kingston in 1975. Having looked through the archives at the Secretariat, it seems to me that this was the forum at which African liberation movements were on the periphery. I know that SWAPO sent a delegation. I understand that both Joshua Nkomo of ZAPU and Robert Mugabe of ZANU were also there. I understand Bishop Abel Muzorewa was there. So this was a different type of meeting.

EA: Well, yes it was, but you see the idea of a Retreat, in my thinking, came from the experience of Singapore. I think Trudeau left Singapore with the belief that the heads of government needed to be alone to deal with very ticklish issues. It was after Singapore following the decision that the next venue would be Ottawa that Trudeau put it to Arnold Smith that in Ottawa there should be a Retreat to allow the heads of government in a more relaxed gathering by themselves alone to deal with ticklish issues, challenging issues. I must tell you that the venue for the Retreat was changed only eight weeks before the meeting. I was the conference secretary then, and had gone to Canada to view the venue for the Retreat with the head of Trudeau’s office. We both went to where they had decided that the retreat would be: Whistler. On arrival in Whistler, I looked around and saw that the arrangements for Heads’ accommodation and dining facilities were in areas where tourists were likely to still remain.

SO: [Laughter]. Because it’s a ski resort and a walking/hiking resort in summer!

EA: Yes indeed a ski resort. The venue had two little squares, and tourists and Heads of Government would have had to be walking through these squares. I was horrified at the thought. First I had to persuade my colleague, the head of Trudeau’s office, (Mr Ducet ?) about the impracticality of Whistler and this was only eight weeks before the meeting. He saw with me when I pointed out the weaknesses of the venue. I then made a telephone call to Arnold Smith to tell him my findings; and Ducet in turn put a telephone call to his Prime Minister. Arnold Smith and Trudeau having been persuaded by both of us that Whistler would not be suitable, Trudeau immediately offered an alternative venue which we then proceeded to visit. It was Lake Okanagan, a wine producing area. When I saw the site and the venue, it seemed suitable to me and I immediately telephoned Arnold Smith to tell him. He and Trudeau agreed, and so the preparations for Lake Okanagan as venue for the Retreat were completed within eight weeks.

SO: In that it was an innovation for the Commonwealth, for Arnold Smith, as a Canadian Secretary General and for Trudeau, as the host, a lot was riding on this.

EA: Oh, yes, and both of them knew the two places. Arnold Smith knew Lake Okanagan and Whistler. Trudeau of course knew the two places too, and so it was easy for them to agree.

SO: Yes, the politics of selecting the Retreat: as you said, providing the right venue and also the right security and privacy for heads of state. Both were important considerations.

EA: Yes.

SO: So how much politics was there around the selection of Kingston as the next Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting at that Ottawa CHOGM?

EA: There wasn’t really. There wasn’t any controversy that I can remember because Michael Manley was a very popular Prime Minister and by then it had become clear that Sonny Ramphal would be chosen as Arnold Smith’s successor.

SO: So a Caribbean location would be appropriate.

EA: That’s right. And the combination of the two factors made it quite easy to choose Kingston.

SO: Was it also that Michael Manley was a luminary in the non-aligned movement, as well? That was an additional factor?

EA: Well, Michael Manley had a lot going for him. He was a fellow intellectual of Trudeau, he was a strong advocate of the Non-Aligned Movement and his government’s policy of friendship with Fidel Castro’s Cuba, which annoyed the Americans, had commanded some respect and admiration from Trudeau. [Laughter]. His standing in the Non-aligned Movement, and also his standing among African heads of government as well as in India was very high; he was therefore a popular choice.

SO: I can see why. And I had mentioned, the attendance, obviously not in full session, but on the periphery, of African liberation movements. Do you recall having any warning that this was going to happen?

EA: Yes, as the conference secretary. I had had some indication from some representatives of the Liberation movements that they were planning to come to Kingston during the CHOGM and had reported that to Arnold Smith. When he proposed to the Heads of Government in executive session that they should allow the representatives of the Rhodesian/Zimbabwean liberation movements to address them, they agreed to hear them in an informal session. To emphasize the informality of the session with the liberation movements, Trudeau insisted that Heads should not sit in their normal places. Heads could sit anywhere they liked, not in their normal places. And Trudeau made the point by moving around the conference table during the session with the Liberation movements’ representatives.

SO: Junior people got very upset? They didn’t know where to go?

EA: Yes. I remember that Trudeau came to occupy the Commonwealth Secretariat’s seat just behind me where a Singaporean official had sat. The official subsequently presented me with a tie for restoring his seat after Trudeau left [laughter].

SO: Did he also put his nameplate upside down? Or turned it over? I had heard that he upended his nameplate in protest.

EA: No, he wasn’t really protesting. He was not objecting to hearing them…

SO: But he was insisting on the informality because –

EA: Yes, he was just making the point that they were not to be heard in a formal session of the Heads presumably because of a precedent being set for Quebec.

SO: Ah, ah. Thank you.

[Laughter].

SO: It’s a while ago. I think that can go on the record.

EA: [Laughter]. Well, I mean Trudeau must have had his own reasons for his extraordinary sensitivity towards liberation fighters.

SO: Connected to that, and please excuse me for interrupting, but were there ever Quebequois delegations around the periphery of Commonwealth meetings?

EA: No, never.

SO: I’m sorry, I just wanted to clarify.

EA: Arnold Smith would never have allowed that. In 1968 I accompanied Arnold Smith on a visit to Canada, which took place barely ten days after the French President Charles De Gaulle’s visit and infamous speech of “Vive Le Quebec! Vive Le Quebec libre!” You remember that. And Canada was on tenterhooks with a growing movement for an independent Quebec. It was the days of Lester Pearson as prime minister. I accompanied Arnold Smith to a meeting with Pearson and some leaders of the Liberal party. You remember that the nature of Canadian politics at the time, was such that Pearson, very boldly, bypassed the stalwarts of the Liberal party, people like John Turner and Paul Martin, the father of the second Paul Martin who subsequently became prime minister. He bypassed them at the Liberal Party Convention to go and choose Pierre Elliot Trudeau, the Quebequois whose parliamentary experience at the time was not more than three years, and whose ministerial experience was just under 18 months as Minister of Justice, during which time the ministry had had a little scandal. [Laughter]. But Pearson wanted him to succeed him in order to save the Canadian union.

And of course Trudeau, when he succeeded Pearson, immediately brought in the legislation that a third of all senior appointments at the level of permanent secretary in the federal civil service had to be French-speaking. The bilingual policy was brought in, that official speeches had to be made in the two official languages. It was not easy for the English speaking Canadians to swallow because at the time this policy came, over 80% of the permanent secretaries were English speaking, but Trudeau was wise enough to say that the English speaking permanent secretaries should remain as supernumeraries in order to sustain experience and competence. I went with Arnold Smith to Canada then and in fact went with him to Quebec for not an easy meeting with Ronnie Leveque who was then the leader of the Quebecois party.

SO: Can I suggest that, because Quebec was a domestic issue, it was imperative that a Secretary General, albeit a Canadian Secretary General, should not be seen in any way to be interfering in the domestic politics? But was there also a particularly supportive intention of Arnold Smith in meeting Ronnie Leveque?

EA: That was a lesson I learned from Arnold Smith in dealing with the Nigerian situation during my time as Secretary General. Arnold Smith drew a line between his role as Commonwealth Secretary General and his duty to his native Canada. And this was the first message he conveyed to his Canadian interlocutors, which made my presence at some of the meetings a little awkward because he was talking with them as a Canadian concerned about the future of his country. He made sure that they regarded his intervention as not being that of the Commonwealth Secretary General, but that of a Canadian who happened to be Commonwealth Secretary General.

SO: So that would place you in an anomalous situation, as an international servant.

EA: That’s why I say that in some of his meetings I felt a little awkward. But I coped with it because I saw myself as being with the Commonwealth Secretary-General who was also a Canadian.

SO: But you said you yourself, when you were Arnold Smith’s emissary or interlocutor in the Nigerian civil war, made the same distinction between your Nigerian nationality and also your regional origins, and your position at the Secretariat.

EA: Yes. During the crisis in my country in the 1990s, I sought to talk to my Nigerian compatriots as a Nigerian who happened to be Commonwealth Secretary General.

SO: But in the late 1960s you were also from the region that was seeking to secede from the Nigerian federation and that placed you in a particular position.

EA: Yes. In October ’68, right in the middle of the civil war, when Arnold Smith was trying to broker peace and had put some proposals to both sides, the Biafran side, my home, was proving a bit difficult and reluctant to accept it. I told Arnold Smith that I was willing to visit home to see the Biafran leader, Emeka Ojukwu. Arnold Smith said “No, that’s very risky.” At that time it was a huge risk to go to Biafra. Emeka Ojukwu and I had been friends since our boyhood and I said to Arnold Smith that I would like to go and talk to him. At that time, flights into Biafra were very hazardous. There were only ‘the mercy flights’, the name which was given to the Roman Catholic charity flights that took off from Holland with medicines. And I remember in October of that year, the flights went about once in two weeks and the next flight following my enquiries was on the day after my second son was admitted to hospital. He was just about three months old and quite ill. I remember my wife asking me, “You really want to leave your baby who is so ill?” And I replied, “If, God forbid, anything were to happen to him because of my absence, he would be counted as one of the victims of the civil war”. She thought it was the “coldest” thing I could ever say.

SO: Oh. As a mother myself, I feel very affected by that statement.

EA: I then left and went into Biafra via Holland and Sao Tome, the Portuguese route, and landed in Biafra at Uli Airport in the middle of the night. I went the next day to Umuahia to see Ojukwu. I told this story in my memoirs. The return flight was even more frightening because the flight again had to take off at midnight and we went to Gabon. I was in an aircraft with little children in such a terrible state of health who were being evacuated by the CARITAS. These planes had no seats; we had to fly sitting or lying on mats.

SO: Were you also acting in any way as Arnold Smith’s particular emissary because of your understanding of the local politics and the local dynamics with those African states that did recognise Biafra’s independence?

EA: No.

SO: These were Tanzania and Zambia.

EA: Yes, Tanzania and Zambia were the two Commonwealth countries that recognised Biafra but I was never involved in their recognition of Biafra. I was careful not to go to Biafra as Arnold Smith’s formal emissary, although by implication this is what I was, because as I said to him, I needed to. I don’t think he wanted to take responsibility for sending me to such dangerous situation, but I insisted on going and he allowed me to go talk with Ojukwu on the basis of his proposal.

SO: Ah, yes. Did you have other diplomatic responsibilities in any way, to talk to the French, who of course were particularly supportive of the Biafran government, or to…?

EA: No, apart from my trip to Biafra, I was not involved in the Secretariat’s efforts to broker peace in the civil war especially because the Nigerian government had petitioned Arnold Smith twice to remove me from the Secretariat.

SO: Yes, the letter from the Permanent Secretary is in Arnold Smith’s papers.

EA: Well before the civil war started in Nigeria, I had come to the Commonwealth Secretariat on secondment as a Nigerian diplomatic officer. So I was still on the books of the Nigerian Foreign Service. At the start of the civil war, the Nigerian federal government required all Nigerian diplomats of Igbo extraction, and I’m Igbo, to take oath of allegiance to the federal government. I refused and formally resigned from the Nigerian diplomatic service. The Nigerian government then petitioned that I should not remain in the Secretariat, but Arnold Smith took the view that I was a collective servant of the Commonwealth. He cited the example that when Czechoslovakia went communist after the revolution in 1948, the new communist government in Czechoslovakia had petitioned Trygve Lie, the first UN secretary general, that the Czechoslovakian officials in the UN secretariat should be removed. But the UN Secretary General said no maintaining that all the UN secretariat staff were international civil servants owing allegiance collectively to the international community. Arnold Smith said to the Nigerian government that Emeka Anyaoku and all his colleagues in the Secretariat were international Commonwealth servants whose allegiance must be owed collectively to the Commonwealth and that he saw no reason to think that I did not owe allegiance to the Commonwealth association. He therefore refused the request.

SO: I’ve read Arnold Smith’s letter of reply which is in his papers, rebutting the criticism from the Nigerian permanent secretary which calls for your removal.

EA: Yes, that was why I told the story in my book of my first meeting with the then Head of State of Nigeria, General Gowon, after the civil war when I went to Nigeria as a special envoy of the Secretary-General to discuss the issue of the admission of the new state of Bangladesh into the Commonwealth.

SO: Yes, and General Gowon asked you about your position during the civil war, and said at the end he respected your honesty.